RGUHS Nat. J. Pub. Heal. Sci Vol No: 17 Issue No: 3 pISSN:

Dear Authors,

We invite you to watch this comprehensive video guide on the process of submitting your article online. This video will provide you with step-by-step instructions to ensure a smooth and successful submission.

Thank you for your attention and cooperation.

1Dr. Vidya Bhat S, Department of Prosthodontics, Yenepoya Dental College, Mangalore, Karnataka, India.

2Practitioner, New Delhi, India

3Department of Prosthodontics, Yenepoya Dental College, Mangalore, Karnataka, India

4Department of Prosthodontics, Yenepoya Dental College, Mangalore, Karnataka, India

5Department of Prosthodontics, Yenepoya Dental College, Mangalore, Karnataka, India

6Department of Prosthodontics, Yenepoya Dental College, Mangalore, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding Author:

Dr. Vidya Bhat S, Department of Prosthodontics, Yenepoya Dental College, Mangalore, Karnataka, India., Email: vidya.bhat@yenepoya.edu.in

Abstract

Aim: To evaluate the effect of wearing N95 face mask and visor on pulse and saturation of dentists over different time intervals.

Methodology: Baseline pulse and oxygen saturation level of healthy participants were checked and recorded using pulse oximeter on the second finger of right hand. All were asked to wear N95 masks and visor, and the mask position did not vary during the procedures (never below the nose). Pulse oximeter values were recorded at the end of every 30 minutes, for a total of 2 hrs.

Result: The pulse and oxygen saturation values obtained were analysed using paired T test. There was a drop in oxygen saturation seen after 60 minutes but it was not statistically significant. There was no significant change in pulse of dentists wearing N95 masks and visors over different time intervals.

Conclusion: Wearing of N95 masks and visor does not have any significant change in pulse and oxygen saturation of dentists over different time intervals.

Keywords

Downloads

-

1FullTextPDF

Article

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the critical role of personal protective equipment (PPE), including visors and N95 masks, in preventing the transmission of infections. The pandemic has fundamentally altered daily life, making mask-wearing a mandatory practice for infection control. This practice has become a part of daily routines, contributing to a comprehensive strategy to reduce transmission and save lives. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides guidelines on the effectiveness of various masks and respirators in preventing COVID-19.1

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) primarily spreads through direct contact with infectious respiratory droplets or fomites, as stated by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2004. Following the SARS outbreak, Peiris et al., identified the main transmission route as direct or indirect contact of mucous membranes (eyes, nose, mouth) with infectious droplets. Infected individuals can produce particles ranging from 0.1 to 100 mm, which can be deposited in the upper and lower respiratory tracts of a susceptible host.2 Most respiratory infections are transmitted through large droplets over short distances or contact with contaminated surfaces.

Tambyah's extensive clinical and literature review concluded that PPE, especially facemasks, is crucial for infection control.3

Dentists are particularly vulnerable to infection due to their proximity to patients and exposure to aerosols. The Dental Council of India (DCI) recommends that dental professionals wear N95 masks or at least 3-ply masks, along with suitable head caps, protective eyewear, and face shields, to ensure safe clinical practice during the COVID-19 outbreak.4

Masks are designed to contain respiratory droplets and provide some protection from particles expelled by others. Respirators are designed to protect the wearer from inhaling particles, including the virus that causes COVID-19, while also containing respiratory droplets to protect others. Various types of masks, such as cloth masks, disposable surgical masks, and respirators, are available to prevent infection spread. NIOSH-approved respirators meet specific U.S. standards, including quality requirements, whereas international standards often lack these requirements. KN95 masks are the most widely available international standard respirators.5

N95 masks filter out 95% or more of airborne particulate matter, offering a close facial fit and efficient filtration. The edges of the mask are designed to form a seal around the nose and mouth. Pulse oximeters provide a non-invasive method of measuring pulse and oxygen saturation levels accurately.6

Some dentists and laypersons report experiencing breathlessness and suffocation from prolonged mask use. This study aims to investigate whether wearing facemasks and visors affects the oxygen saturation levels in dentists over extended periods.

Materials and Methods

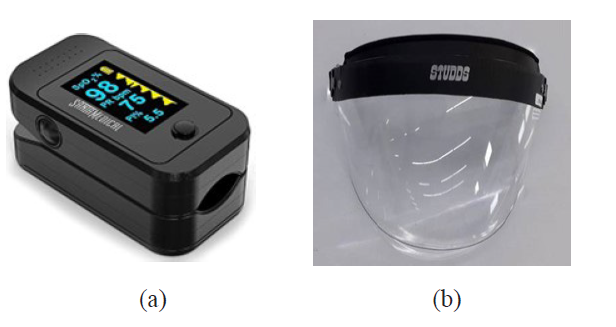

After obtaining ethical clearance from Institution and consent from participants, 55 healthy post graduate students at a Dental College, between the age of 25 to 35 of either sex were enrolled for our study. Participants with lung disease, cardiac disease and smokers were excluded from the study. Sample size is calculated using G-power software with the level of significance: Alpha = 5%, Power 1 - beta = 90%, Effect size d = 0.4. The pulse oximeter (Figure 1) readings were validated against a patient monitor in hospital before starting the study for accuracy baseline pulse and oxygen saturation level were checked and recorded using pulse oximeter on the second finger of right hand. Instructions were given. The participants were asked to wear the mask and the time noted. N95 masks and face visor (Figure 1) were used by all the dentists and the mask position did not vary during the procedures (never below the nose).

Participants were encouraged to speak and behave in their usual manner throughout the routine work. If the participants felt suffocated or breathless during the study period, they were allowed to remove mask and visor after noting down the time elapsed. At the end of every 30 minutes pulse oximeter was applied again and the values were recorded for a total of 2 hrs. Total of 5 values were obtained- 0, 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes (Table 2).

Results

The readings were obtained at baseline, 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes and noted down for statistical evaluation. (Table 1). T test was done for statistical analysis to compare the pulse and oxygen saturation at different time intervals.

The graph 1 shows that there is a rise in oxygen saturation at 60 minutes which drops down at 90 minutes and then again rises. The change in oxygen saturation at different time intervals was not statis-tically significant.

The graph 2 shows rise and drop of pulse rate at various time intervals. At 120 mins there was a rise in the pulse rate, but the changes in pulse rates were not statistically significant.

From the Table 2 it was inferred that there was no significant change in the pulse (P-0.90) and oxygen saturation (P-0.83) and not statistically significant. Hence the N95 masks and visors had no effect on the pulse and oxygen saturation of dentists even if continuously worn for 2 hours or longer.

Discussion

Understanding how illnesses spread and taking preventive measures are the best defenses against transmission. Protecting oneself from COVID-19 involves maintaining a minimum distance of one meter from others, using a properly fitting mask, regularly cleaning hands or using an alcohol-based rub and getting vaccinated. When an infected person coughs, sneezes, speaks, sings or exhales, they can release tiny liquid particles from their mouth or nose that may carry the virus. These particles can be tiny aerosols or larger respiratory droplets. Practicing respiratory etiquette, such as coughing into a flexed elbow and staying home when feeling unwell are also crucial.7

ASTM F3502-21 describes a barrier covering as a device worn over the face to cover the nose and mouth. Its primary function is to control the source of particulate matter and reduce inhaled particles. However, barrier face coverings are not substitutes for N95 respirators and other filtering facepiece respirators (FFRs) or surgical masks, which offer higher levels of protection.8

N95 respirators are designed to fit closely to the face and filter airborne particles effectively. Surgical N95 respirators, often used in healthcare settings, belong to a specific category of N95 FFRs. While N95 respirators provide better protection, they may be less comfortable than surgical masks, which are more breathable due to higher water vapor and air permeability.6

Qian et al., studied the penetration efficiency of N95 respirators for airborne particles and concluded that N95 respirators offer excellent protection with a good face seal. They found that N95 masks have a filtration efficiency of 99.5% or higher for particles larger than 0.75 mm and a minimum efficiency of 95% for particles sized 0.1-0.3 mm. N95 respirators have about 2% higher filtration efficiency than surgical masks, showing that both can provide effective protection in low viral load environments.9

Face masks have become essential, providing public reassurance. Initially, cloth masks were thought to provide limited filtration of virus-sized aerosol particles, whereas face shields were found to reduce immediate viral exposure by 96% when worn within 18 inches of a cough.6

Pulse oximetry measures the ratio of pulsatile to total transmitted red light versus infrared light to determine arterial oxygen saturation.2 Various factors, such as anemia, light scattering, and tissue pulsation, can affect the accuracy of pulse oximeters. Accurate pulse oximeters require empirically determined correction factors obtained through in vivo testing. Many low-cost pulse oximeters lack these testing, raising concerns about their accuracy. However, accurate and affordable pulse oximeters can be developed, as demonstrated by various studies.10,11

Wearing N95 masks can trap heat and moisture, and some exhaled CO2, potentially reducing blood oxyge-nation. Normal blood oxygen saturation ranges from 90 to 97.5%, corresponding to an arterial oxygen partial pressure of 13.3 to 13.7 kPa.12 Oxygen saturation below 95% at rest is considered unusual, and levels below 90% can lead to serious deterioration, with levels under 70% being life-threatening.13,14

Normal pulse rates range from 60 to 100 beats per minute. Decreased oxygen saturation and increased pulse rate can be associated with exposure to fine particles. Heart rate acceleration may result from impaired autonomic cardiac control or hypoxia.15

In the study, no significant changes in pulse and oxygen saturation were observed after wearing masks for different time periods (P > 0.05). However, further evaluation with a larger sample size and longer durations, especially for dentists who often wear masks for over 8 hours a day are needed.

Conclusion

This study aimed to investigate the impact of wearing face masks and visors on the oxygen saturation levels and pulse rates of dentists. The findings from our study have provided several important insights into this topic. First and foremost, our research revealed that there was no statistically significant change in either pulse rates or oxygen saturation levels among the dentists, even after wearing masks and visors for various time intervals. These results are reassuring, suggesting that the use of proper PPE, including masks and visors, does not compromise the overall health and well-being of healthcare professionals. However, it is important to note that the findings of our study were limited to short time intervals and the study population may not fully represent the diverse range of healthcare professionals and the general population. Dentists, in particular, often wear masks for extended periods exceeding 8 hours a day, and further studies are needed to assess the potential long-term effects of mask-wearing on their health and well-being. This knowledge will be invaluable in refining infection control guidelines and ensuring the wellbeing of those on the front lines of healthcare, especially in the face of ongoing health crises like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conflict of Interest

Nil

Supporting File

References

1. Martinelli L, Kopilaš V, Vidmar M, et al. Face Masks During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Simple Protection Tool With Many Meanings. Front Public Heal 2021;13;8:606635.

2. World Health Organization. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): Status of the outbreak and lessons for the immediate future. [Online] 2003[cited 20 October 2024]. Available from: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) - multi-country outbreak - Update 27. World Heal Organ 2003;40:1-10.

3. Li Y, Wong T, Chung J, et al. In vivo protective performance of N95 respirator and surgical facemask. Am J Ind Med 2006;49(12):1056-65.

4. DENTAL COUNCIL OF INDIA. Precautionary and preventive measures to prevent spreading of Novel Coronavirus (COVID- 19) - Regarding. [online] 2020. [cited April 17, 2024]. Available from:https:// d c i i n d i a . g o v. i n / A d m i n / N e w s A r c h i v e s / L . No._8855..PDF

5. I3CGlobal. NIOSH Certification for N95 Respirator. [online] [cited April 17, 2024]. Available from: https://www.i3cglobal.com/niosh-certification/

6. Smith RN, Hofmeyr R. Perioperative comparison of the agreement between a portable fingertip pulse oximeter v. a conventional bedside pulse oximeter in adult patients (COMFORT trial). S Afr Med J 2019;109(3):154-8.

7. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19).[online] [cited April 17, 2024]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1

8. ASTM International. Standard Specification for Barrier Face Coverings. ASTM F3502-21[online] 2022. [cited April 17, 2024]. Available from: https://www.astm.org/f3502-21.html

9. Qian Y, Willeke K, Grinshpun et al. Performance of N95 Respirators: Filtration Efficiency for Airborne Microbial and Inert Particles. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J 1998;59(2):128-32.

10. Lipnick MS, Feiner JR, Au P, et al. The Accuracy of 6 Inexpensive Pulse Oximeters Not Cleared by the Food and Drug Administration. Anesth Analg 2016;123(2):338-45.

11. Edward D. Chan, Michael M. Chan, Mallory M. Chan. Pulse oximetry: Understanding its basic principles facilitates appreciation of its limitations. Respir Med, 2013;107(6):789-799.

12. Beder A, Büyükkoçak Ü, Sabuncuoǧlu H, et al. Preliminary report on surgical mask induced deoxygenation during major surgery. Neurocirugia 2008;19(2):121-6.

13. Hafen BB, Sharma S. Oxygen Saturation. [Updated 2022 Nov 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525974

14. Peterson BK. Vital Signs. In: Physical Rehabilitation Elsevier; 2007. p. 598-624.

15. C. Arden III Pope, Dockery DW, Kanner RE, et al. Oxygen saturation, pulse rate, and particulate air pollution: A daily time-series panel study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159(2):365-72.