RGUHS Nat. J. Pub. Heal. Sci Vol No: 17 Issue No: 3 pISSN:

Dear Authors,

We invite you to watch this comprehensive video guide on the process of submitting your article online. This video will provide you with step-by-step instructions to ensure a smooth and successful submission.

Thank you for your attention and cooperation.

1Specialist Endodontist, Muscat, Oman

2Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Krishnadevaraya College of Dental Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

3Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Krishnadevaraya College of Dental Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

4Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Krishnadevaraya College of Dental Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

5Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Krishnadevaraya College of Dental Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

6Dr. Bhargavi Krishnaraj, Krishnadevaraya College of Dental Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

*Corresponding Author:

Dr. Bhargavi Krishnaraj, Krishnadevaraya College of Dental Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka, India., Email: bhargavikrishnaraj@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Access cavity preparation is the first and most critical stage of root canal treatment. Contracted endodontic cavities (CECs), derived from the concept of minimally invasive dentistry, aim to preserve pericervical dentin and the soffit; however, this design may influence the geometric parameters of canal shaping.

Aim: This study aimed to assess the effects of CECs on the root canal geometry of curved canals prepared using the TruNatomy file system.

Methods: Thirty human mandibular molars with completely developed mesial canals and apices were extracted and randomly divided into two groups: Group 1 - Traditional endodontic cavity (TEC) and Group 2 - Contracted endodontic cavity (CEC). Root canal preparation in both the groups was performed using the TruNatomy file system. Irrigation was carried out with 3% sodium hypochlorite and 17% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scans were obtained prior to and following canal shaping to evaluate changes in canal geometry. The images were analysed using CS 3D software (Carestream Health, Rochester, NY, USA) to assess centroid shift at 3 mm, 6 mm, and 9 mm levels from the apex.

Results: The TruNatomy file system demonstrated a slight deviation from the canal centre in the CEC group compared to the TEC group.

Conclusion: Within the parameters of this investigation, TruNatomy files exhibited minor deviation from the canal centre in CECs compared to TECs. Nevertheless, the observed deviations were within the acceptable limits.

Keywords

Downloads

-

1FullTextPDF

Article

Introduction

Endodontic therapy comprises of a variety of technically sound, scientific procedures. Unquestionably, the access cavity is the most crucial technical stage. If not properly done, it can greatly impact the root canal's subsequent preparation.1 Contracted endodontic cavities (CECs), derived from minimally invasive dentistry, serve as an alternative to traditional endodontic cavities (TEC), and are designed to preserve the mechanical stability of the tooth.2 Recently, TruNatomy (DentsplySirona) developed a new generation of rotating file system comprising five distinct instruments with unique designs, featuring a sophisticated post-grind thermal treatment with three shaping files, with an off-centered parallelogram cross-section and a regression taper, with a minimum diameter of 0.8 mm. TruNatomy files integrate file shape, a regressive taper, and a thin, extremely flexible wire to allow for effective root canal therapy, even in curved cavities and without straight line access, such as in contracted access cavities, while helping to preserve structural dentin.3,4

Medicine and dentistry are progressing toward minimally invasive procedures that offer significant benefits to patients. For minimally invasive interventions to become widely adopted, their advantages must outweigh potential risks, supportive technologies must be developed, and clinicians’ skills must be adapted to operate effectively within confined spaces. Technological advances such as cone beam computed tomography (CBCT), operating microscopes, and nickel-titanium (NiTi) instruments have been instrumental in enabling this progress.5

While lacking “convenience form,’’practitioners must ensure thorough debridement of all pulp tissue from the root canal system, including the pulp chamber, and prevent procedural errors. However, the purported advantages of this approach remain insufficiently supported by current research.

Thus, the objective of the present study was to evaluate the centering ability and canal transportation in order to determine the effect of limited endodontic access on the root canal geometry of curved canals prepared using the TruNatomy file system.

Materials and Methods

In accordance with approval from the local ethics committee, freshly extracted mandibular first permanent molars exhibiting complete apical development were used.

Sample Size Estimation

A sample size of 15 specimens per group was calculated using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.2.) to achieve a study power of 80%, with a 5% margin of error, resulting in a total sample size of 30.

Preparation of Tooth Sample

After debridement of the root surface, the specimens were stored in saline. TECs were prepared in 25 samples (Group 1) and CECs were prepared in 25 samples (Group 2) using an endodontic access bur no. 2, under a dental operating microscope (Figure 1). The mesiobuccal canals were explored by inserting a K file #10 until the file tip became just visible at the apical foramen. The working length was determined by subtracting 1 mm from this measurement. To standardize the working length at 18 mm, the mesiobuccal cusps (reference cusp) of all samples were flattened.

The degree of curvature of the mesiobuccal canal was determined using Schneider’s method, by aligning the X-ray tube head perpendicularly to the root canal. A total of 30 teeth with mesiobuccal canal curvatures ranging between 20-40 degrees were included in the study, comprising 15 teeth with TECs and 15 with CECs.

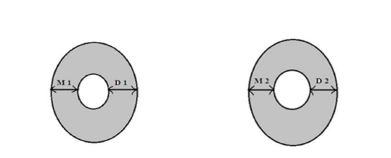

The teeth were mounted on custom-made putty index blocks, and CBCT images were obtained before instrumentation. The images were analysed using a third-party software (CS 3D, Carestream Health, Rochester, NY, USA). The degree of canal curvature was reconfirmed on the CBCT images. The shortest distances from the mesiobuccal canal wall to the mesial (M1) and distal (D1) aspects of the canal were measured at three different levels - 3 mm, 6 mm, and 9 mm from the apical end of the root (Figure 2). All data were stored on a compact disc.

Group I (n=15) - TEC: The mesiobuccal canals were cleaned and shaped using TruNatomy files according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The TruNatomy orifice modifier was utilized to create and redefine the coronal opening. To establish a reproducible glide path, a size 10 K-file was taken to the full working length. The microglide path was then expanded using the TruNatomy Glider with three easy amplitudes in a single pass. TruNatomy (26/04) prime file was used for the final preparation.

Group II (n=15) - CEC: The mesiobuccal canals were cleaned and shaped using TruNatomy files according to the manufacturer’s instructions, as in Group 1. A 3% sodium hypochlorite solution was used for irrigation between instrumentation steps, and RC Prep was used as a lubricant during canal preparation. After completion of instrumentation, 1 mL of 17% ethylenedi-aminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) was applied for one minute, followed by a final rinse with saline.

Following instrumentation, CBCT pictures were acquired. The mesiobuccal canal's mesial (M2) and distal (D2) directions were measured at three different levels - 3 mm, 6 mm, and 9 mm from the apical end of the root, and the data were recorded on a compact disc.

Assessment of Canal Transportation

The following formula was used to evaluate canal transportation:

(M1 – M2) – (D1 – D2)

- Positive result indicates transportation towards the mesial portion.

- Negative result correspond to transportation towards the distal portion.

- Null result indicates absence of transportation.

Assessment of Centering Ability

Centering ability was evaluated using the following formula:

(M1 – M2) / (D1 – D2) or (D1 – D2) / (M1 – M2)

A result of ‘1’ indicates perfect centralization capacity. The smaller value was regarded as the ratio's numerator if the values were unequal. The closer the result was to zero, the lower the instrument's ability to maintain its position along the centre axis of the canal.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, Version 22.0. (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA; released in 2013) was used to perform statistical analysis.

Descriptive analysis was conducted to express centering ability and canal transportation as mean and standard deviation (SD) values for each study group.The Mann- Whitney U test was used to compare the mean centering ability and canal transportation at different levels from the apex between the TEC and CEC groups. Friedman's test was used to compare the mean centering ability and canal transportation between different lengths from the apex in each study group.The level of significance was set at P <0.05.

Results

Canal Centering Ability

The test results demonstrated a comparison of the mean centering ability between the two groups. The mean centering ability of the TEC group at 3 mm, 6 mm, and 9 mm was relatively higher (0.91 ± 0.60, 0.88 ± 0.85, and 1.17 ± 0.88, respectively) compared to the CEC group (0.52 ± 0.72, 0.73 ± 0.80, and 0.73 ± 0.86, respectively). However, no significant differences were noted in the mean centering ability between the two groups at any level from the apex (Table 1).

The test results demonstrated a comparison of the mean centering ability at different levels from the apex within each study group. For TEC group, the mean centering ability at 3 mm, 6 mm, and 9 mm was 0.91 ± 0.60, 0.88 ± 0.85, and 1.17 ± 0.88, respectively. For the CEC group, the corresponding values were 0.52 ± 0.72, 0.73 ± 0.80, and 0.73 ± 0.86. However, no significant differences in the mean centering ability were observed among the different levels from the apex in either study group (Table 2).

Canal Transportation

The test results demonstrated a comparative analysis of the mean canal transportation between the two groups. The mean canal transportation values for the TEC group at 3 mm, 6 mm, and 9 mm were relatively higher 0.02 ± 0.06, 0.00 ± 0.12 ,and 0.03 ± 0.10, respectively, whereas for the CEC group, the corresponding values were 0.01 ± 0.13, -0.02 ± 0.10, and 0.01 ± 0.10. However, no significance differences were noted in the mean canal transportation between the two groups at any level from the apex (Table 3 and Table 4).

The test results demonstrated a comparative analysis of the mean canal transportation at different levels from the apex within each study group. For the TEC group, the mean canal transportation at 3 mm, 6 mm, and 9 mm was 0.02 ± 0.06, 0.00 ± 0.12, and 0.03 ± 0.10, respectively. For the CEC group, the corresponding values were 0.01 ± 0.13, -0.02 ± 0.10, and 0.01 ± 0.10. However, no significant differences in mean canal transportation were observed among the different levels from the apex in either study group (Table 4).

Discussion

An ideal access cavity facilitates proper irrigation and effective instrumentation of the root canal system,thereby influencing the overall success of endodontic therapy.7,8,2

Although endodontic procedures may reduce a tooth's resistance to fracture, preserving maximal tooth structure can improve the prognosis of teeth subjected to cyclical occlusal forces.9

Traditional endodontic cavities (TEC) have been disassociated from restorative and structural considerations, becoming primarily endodontic-centric and operator-focused.10 TECs emphasize on creating a straight-line pathway that allows complete removal of pulp chamber contents, visualization of the pulp chamber floor and canal orifices, and the introduction of instruments with direct access to the apical one-third of the canal for preparation and obturation of the canals.11

As an alternative to TEC, the contracted endodontic cavity (CEC) has been proposed to maintain the mechanical stability of the tooth. It has been suggested that coronal interferences associated with CECs may pose operating challenges during canal shaping.2 One of the defining features of CECs is the restricted access area, which can increase procedural difficulty but helps preserve tooth structure, potentially enhancing resistance to fracture. The CEC outline form generally follows the pulp anatomy, partially maintaining the pulp chamber soffit.12 Instead of sacrificing ease and extension for prevention, nonextended TEC outlines are primarily dictated by orifice positions, providing a more radial and direct pathway. This study evaluated the impact of CEC design on root canal geometry using the TruNatomy file system.

The results demonstrated that the TEC group exhibited higher centering ability at 3 mm, 6 mm, and 9 mm compared with the CEC group. The mean centering ability values for the TEC group at 3 mm, 6 mm, and 9 mm were 0.91 ± 0.60, 0.88 ± 0.85, and 1.17 ± 0.88, respectively, while the corresponding values for the CEC group were 0.52 ± 0.72, 0.73 ± 0.80, and 0.73 ± 0.86. However, no statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups at any level from the apex.

In the present study, the TEC group showed better centering ability than the CEC group. This finding is consistent with the results reported by Alovisi et al. The centroid shift observed in the CEC group may have been caused by coronal interferences, which increased the number of instrument motions needed to reach the working length and subjected the instrument to excessive pressure against the outer aspect of the root canal curvature.2 The restricted access cavity design might also have contributed to greater difficulty in debris removal during shaping, potentially affecting the instrument’s performance.3

Precurving the instrument can reduce the stress exerted on the instrument.13 Chan et al., and Hankins et al., reported that it is preferable to enter canals using files that have been pre-bent.14,15 The ability to precurve the TruNatomy files may have facilitated smoother entry even in constricted cavities, allowing the file to negotiate canal curvatures more effectively and with reduced lateral stress.

TruNatomy files feature an off-centered cross-sectional design that produces a snake-like, swaggering movement during rotation, thereby reducing the stress generated on the instrument. Limited contact between the instrument and the canal wall decreases screw-in forces and provides additional space for effective removal of debris. Hong et al., evaluated the geometric effects of various off-centered NiTi rotary instruments and concluded that Protaper Next, which possesses a rectangular off-centered cross section, demonstrated superior performance among the instruments tested.12,16

Studies have shown that canal transportation has undesirable effects, like improper canal preparation leading to inefficient sanitization and loss of the apical stop, which may result in extrusion of irrigating solutions or obturation materials, causing irritation to the periapical tissues.17,19 It may also result in inadequate canal taper, which could impede effective cleaning and obturation of the apical third of the root canal, thereby compromising the overall success of root canal treatment.18

Evaluation of changes in canal shape after instrumentation is a reliable method for assessing the performance of shaping techniques and instruments used.20,21 The regressive taper, slender design, and extremely flexible file geometry enable effective root canal therapy, even in cases lacking straight-line access or presenting with curved canals. The manufacturer also recommends the use of TruNatomy files in conservative endodontic access cavities.3

In the present study, the mean canal transportation values for the TEC group at 3 mm, 6 mm, and 9 mm were relatively higher (0.02 ± 0.06, 0.00 ± 0.12, and 0.03 ± 0.10, respectively) compared to the CEC group (0.01 ± 0.13, -0.02 ± 0.10, and 0.01 ± 0.10). However, no significant differences were noted between the two groups at any level from the apex.

The lower canal transportation observed in the CEC group may be attributed to the slim NiTi file design (0.8 mm instead of 1.2 mm) and regressive taper of TruNatomy files that minimizes the removal of coronal dentin and prevents excessive thinning of the radicular walls toward the danger zones. When considering canal transportation, the use of less tapered instruments may therefore be advantageous, particularly in the mesial roots of mandibular molars.22

Ideally, a straight line access to the apical foramen reduces the likelihood of canal transportation, as compared to CEC.23 However, in the present study, the results were more favourable for the CEC group than for the TEC group. This outcome may be attributed to the innovative parallelogram cross-sectional design of the TruNatomy files, which provide only two point contact with the canal walls and a smaller cross-sectional area, thereby enhancing the flexibility of file.4 However, no significant difference was detected between the two groups.

The diameter of the core and the cross-sectional area of nickel titanium (NiTi) files substantially influence their shaping ability. The regressive taper of TruNatomy files contributes to dentin preservation along the working length, thereby minimizing canal transportation.

Kataia et al., (2018) analyzed canal transportation using WaveOne Gold and Reciproc Blue in simulated root canals with varied kinematics. Their findings demonstrated that Reciproc Blue, with its regression taper design, showed noticeably less transportation.24

To date, no studies reported have compared canal transportation between TEC and CEC designs. Moore B et al., using micro computed tomographic imaging, examined the effect of constricted endodontic cavities on the efficiency of instrumentation and the biomechanical behavior of maxillary molars, where canals were instrumented with V Taper2H (SS White Dental, Lakewood, NJ) both in TEC and CEC groups. Their results showed that CECs did not adversely impact instrumentation efficacy or biomechanical performance. These outcomes were attributed to the V Taper 2H instrument's regressive taper design, smaller D12 diameter (0.64 mm for 20/.06), and increased flexibility of the instrument.25

As the concept of minimally invasive endodontics is gaining popularity, instruments with reduced taper, such as TruNatomy files, may be preferred to minimize root canal transportation. The orifice modifier, with a smaller coronal diameter of 0.8 mm compared to the Protaper Next SX instrument, helps preserve peri-cervical dentin and the soffit, thereby structurally reinforcing the tooth. This contrasts with traditional straight line access preparations that utilize larger diameter orifice openers.

Gaikwad et al., evaluated the strength of endodontically treated teeth following the preservation of the soffit and pericervical dentin. They concluded that these teeth exhibited superior structural integrity compared to those with straight line access. Furthermore, they reported that the Clark-Khademi access preparation was superior to traditional straight-line access in terms of dentin preservation and tooth strengthening.26

Dentin conservation increases the fracture resistance of the endodontically treated teeth. The TruNatomy file system incorporates less tapered instruments, which help in preserving peri cervical dentin, the soffit, and dentin in both the middle and apical thirds of the root, thereby conserving tooth structure and potentially enhancing fracture resistance. Makati et al., investigated the residual dentin thickness and fracture resistance associated with conventional and conservative access cavity designs and biomechanical preparations in molars, utilizing cone-beam computed tomography. They concluded that dentin conservation resulted in increased resistance to fracture in the conservative group, nearly doubling it compared to the conventional group.27

In the present study, no instrument separation was observed. Although there is a high risk of instrument fracture when accessing canals through a restricted opening, no such occurrences were noted, likely due to the use of TruNatomy system, which exhibits higher resistance to fatigue.

The study was conducted on groups with specific inclusion and exclusion criteria; however, despite careful selection, complete standardization of canal morphology in extracted teeth could not be achieved.

Conclusion

Within the limitation of this study, it can be concluded that the centering ability was superior in TEC, whereas canal transportation was lower in CEC when using the TruNatomy file system. As no statistically significant differences in canal geometry were observed between TEC and CEC in the mesiobuccal canals of mandibular molars prepared with TruNatomy files, these innovative instruments can be effectively used in CEC designs, supporting the principles of minimally invasive endodontics.

Acknowledgement

Nil

Conflict of Interest

Nil

Supporting File

References

1. Ruddle CJ. Endodontic access preparation: an opening for success. Dentistry Today 2007;26(2):114.

2. Alovisi M, Pasqualini D, Musso E, et al. Influence of contracted endodontic access on root canal geometry: an in vitro study. J Endod 2018;44(4): 614-20.

3. Dentsply Sirona. TruNatomy: A total solution to respect the true, natural anatomy [Internet]. Charlotte (NC): Dentsply Sirona; 2019 [cited 2025 Nov 04]. Available from: https://www.dentsplysirona. com/content/dam/master/regions-countries/north-america/product-procedure-brand/endodontics/ brands/trunatomy/END-Brochure-TruNatomy- EN.pdf

4. Van der Vyver PJ, Vorster M, Peters OA. Minimally invasive endodontics using a new single-file rotary system. Int Dent-African ed. 2019;9(4):6-20.

5. Lamata P, Ali W, Cano A, et al. Augmented reality for minimally invasive surgery: overview and some recent advances. In: Maad S, editor. Augmented Reality. Rijeka: IntechOpen; 2010.

6. Pasternak‐Júnior B, Sousa‐Neto MD, Silva RG. Canal transportation and centring ability of RaCe rotary instruments. Int Endod J 2009;42(6): 499-506.

7. Adams N, Tomson PL. Access cavity preparation. Br Dent J 2014;216(6):333-9.

8. Gambarini G, Krasti G, Chaniotis A, et al. Clinical challenges and current trends in access cavity design and working length determination. First European Society of Endodontology (ESE) Clinical Meeting: ACTA, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. Int Endod J 2019;52:397-99.

9. Pereira JR, McDonald A, Petrie A, et al. Effect of cavity design on tooth surface strain. J Prosthet Dent 2013;110(5):369-75.

10. Clark D, Khademi J. Modern molar endodontic access and directed dentin conservation. Dent Clin North Am 2010;54(2):249-73.

11. Habib A, Abdulrab A, Doumani M, et al. Knowledge and practice of access cavity preparation among senior dental students. IOSR-JDMS 2017;16(6): 108-11.

12. Marchesan MA, Lloyd A, Clement DJ, et al. Impacts of contracted endodontic cavities on primary root canal curvature parameters in mandibular molars. J Endod 2018;44(10):1558-62.

13. Carvalho LAP, Bonetti I, Borges MAG. A comparison of molar root canal preparation using stain-less-steel and nickel-titanium instruments. J Endod 1999;25(12):807-10.

14. Chan AW, Cheung GS. A comparison of stainless steel and nickel‐titanium K‐files in curved root ca-nals. Int Endod J 1996;29(6):370-5.

15. Hankins PJ, ElDeeb ME. An evaluation of the canal master, balanced-force, and step-back techniques. J Endod 1996;22(3):123-30.

16. Ha JH, Kwak SW, Versluis A, et al. The geometric effect of an off-centered cross-section on nickeltitanium rotary instruments: A finite element analysis study. J Dent Sci 2017;12(2):173-8.

17. Wu MK, Fan B, Wesselink PR. Leakage along apical root fillings in curved root canals. Part I: effects of apical transportation on seal of root fillings. J Endod 2000;26(4):210-6.

18. Hülsmann M, Peters OA, Dummer PM. Mechanical preparation of root canals: shaping goals, techniques and means. Endod Topics 2005;10(1):30-76.

19. Haapasalo M, Shen Y. Evolution of nickeltitanium instruments: from past to future. Endod Topics 2013;29(1):3-17.

20. Bürklein S, Mathey D, Schäfer E. Shaping ability of Pro Taper NEXT and BT‐R a C e nickeltitanium instruments in severely curved root canals. Int Endod J 2015;48(8):774-81.

21. Pasqualini D, Alovsi M, Cemenasco A, et al. Microcomputed tomography evaluation of Protaper Next and BioRace shaping outcomes in maxillary first molar curved canals. J Endod 2015;41(10): 1706-10.

22. Kandaswamy D, Venkateshbabu N, Porkodi I, et al. Canal-centering ability: An endodontic challenge. J Conserv Dent 2009;12(1):3-9.

23. Bürklein S, Schäfer E. Critical evaluation of root canal transportation by instrumentation. Endod Topics 2013;29(1):110-24.

24. Kataia MM, Roshdy NN, Nagy MM. Comparative analysis of canal transportation using reciproc blue and wave one gold in simulated root canals using different kinematics. Future Dental Journal 2018;4(2):156-9.

25. Moore B, Verdelis K, Kisben A, et al. Impacts of contracted endodontic cavities on instrumentation efficacy and biomechanical responses in maxillary molars. J Endod 2016;42(12):1779-83.

26. Gaikwad A, Pandit V. In vitro evaluation of the strength of endodontically treated teeth after preservation of soffit and pericervical dentin. IP Indian J Conserv Endod 2016;1(3):93-6.

27. Makati D, Shah NC, Brave D. Evaluation of remaining dentin thickness and fracture resistance of conventional and conservative access and bio-mechanical preparation in molars using cone-beam computed tomography: An in vitro study. J Conserv Dent 2018;21(3):324.